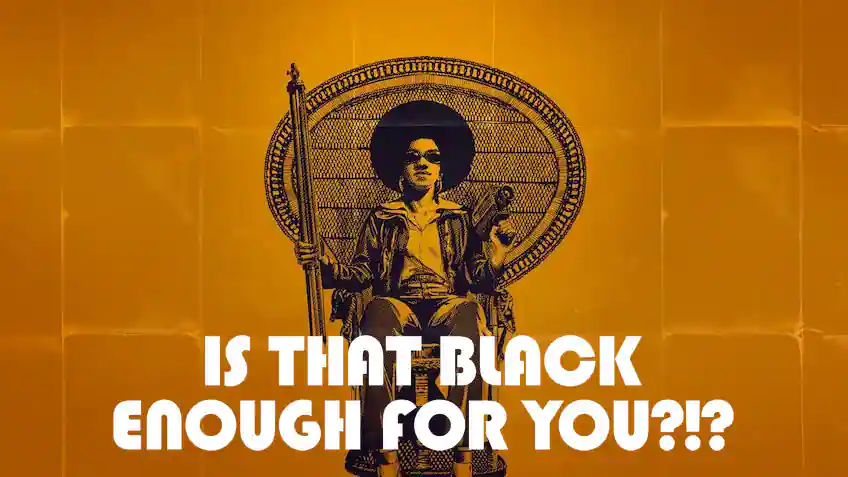

So passionate is Elvis Mitchell’s approach in the Netflix documentary “Is That Black Enough for You?!?” you might find yourself wondering whether the punctuation in the title is a typo. Shouldn’t that be two exclamation points and one question mark rather than the other way around?

“Black Enough” starts streaming Nov. 11.

The documentary looks at how Black cinema flourished in the years between 1968 and 1978. “For me,” Mitchell says, this is “the most exciting period in the history of film.”

The flourishing extended beyond the very rough and very tumble genre known as Blaxploitation, typified by such vigorously transgressive titles as “Shaft” (1971), “Super Fly” (1972), and “Foxy Brown” (1974). There were also such very different movies as Gordon Parks’s autobiographical drama “The Learning Tree” (1969); the action-comedy “Cotton Comes to Harlem” (1970), in which “Is that Black enough for you?!” is a recurring punch line; the Billie Holiday biopic “Lady Sings the Blues” (1972), with Diana Ross earning a best actress Oscar nomination in her screen debut; the romantic comedy drama “Claudine” (1974), which also earned Diahann Carroll a best actress Oscar nomination; the Broadway musical adaptation “The Wiz” (1978); and “Killer of Sheep” (1978), Charles Burnett’s magnificent, and still woefully neglected, domestic drama.

Mitchell, who wrote and directed “Black Enough,” doesn’t limit the documentary to those 10 years. It looks ahead to more recent examples of Black filmmaking, arguing for the era’s ongoing influence. It also gives a fine précis of earlier Black cinema, not just the demeaning stereotypes associated with such character actors as Stepin Fetchit and Manton Moreland but also the achievement of independent filmmaker Oscar Micheaux and the painfully thwarted career of Dorothy Dandridge.

“Black Enough” is smart, lively, and sprawling. Watch it with pen and paper handy. There are many (many) film clips, and you’ll hear about lots of movies you’re likely unaware of. More than a few are worth tracking down, though not as many as Mitchell would have you think. The documentary combines history lesson, film criticism, and polemic, which makes for a potent blend.

Mitchell, a film critic and media personality, can offer keen, pithy insights. Blaxploitation was “a term that offered acknowledgment and dismissal” both. For Black filmmakers and actors, these years were a classic instance of “talent seizing opportunity.” “‘Shaft’ wasn’t just a debut. It was an announcement.” Some of Mitchell’s pronouncements seem more dubious. Are Mickey Mouse and Bugs Bunny really versions of minstrelsy? “Black film redeemed the idea of heroic masculinity.” That depends on how you define “masculinity” and definitely on how you define “heroic.” Redemptive is not a concept generally associated with the filmographies of Fred Williamson and Jim Brown.

Mitchell, an engaging narrator, isn’t afraid to name-drop — e.g., “Toni Morrison once told me. . . . ” Or there’s his mentioning how he pointed out to Sidney Poitier that in all five films Poitier directed in the ‘70s the actor played characters impersonating someone else. “Young man,” Mitchell tells us Poitier replied, “I already have a therapist. I don’t need another one.” It’s a good story, though a mite . . . self-serving?

Poitier, who died in January, is one of the documentary’s heroes. Another is Pam Grier, the empress of Blaxploitation. Neither is among the interviewees in “Black Enough,” but two other heroes are, Burnett and Harry Belafonte. Other talking heads include Laurence Fishburne, Samuel L. Jackson, Zendaya (whose presence seems little more than an attempt to get the youth audience), and Whoopi Goldberg. “These movies were about us,” Goldberg says.

Mario Van Peebles relates some stories about his father, Melvin Van Peebles, the director of such crucial films as “Watermelon Man” (1970) and “Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song” (1971), that are funny and telling both. In a talking-head class of his own is Billy Dee Williams, Ross’s costar in “Lady Sings the Blues.” He gets off the single best line in the documentary. Certainly, it’s the most endearing.

“When I walked down those stairs [even] I fell in love with myself,” Williams says of his entrance in “Lady.” “Goodness, gracious, I was smitten.” He could also be describing how Mitchell sees this era. Among the many virtues of “Black Enough” is that even if you don’t feel quite so strongly about that time as Mitchell does, it makes you share his excitement.

![]()

![]()